- Home

- Sean Smith

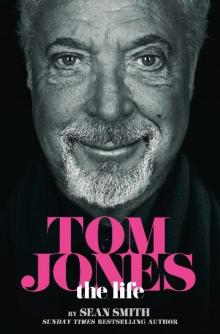

Tom Jones - the Life Page 21

Tom Jones - the Life Read online

Page 21

The next time Glynis travelled with Dai to the US was when Tom was appearing in Atlantic City in 1995. She loved the hotel there, because it was right on the beach. Tom and Dai would put their bathers on, travel down in the lift and then walk across for a swim and a mess about in the sea – much to the surprise of other guests, who didn’t expect to see Tom Jones in the surf.

Tom took the attentions of people desperate to have a picture with him or get an autograph with good grace. Glynis never saw him refuse a photograph, even if he was walking through the casino in the small hours of the morning. She asked Tom if the fans ever got on his nerves. ‘No,’ he replied, ‘because when they stop asking me, I know I’m on my way down.’

One of the things that Tom liked about Dai and Glynis was that they didn’t abuse his hospitality. If Glynis needed to phone home, she would do it from the lobby and not from the room, where it would be charged to his bill. Similarly, when she bought small items, like suncream, she would pay cash. Dai never gambled and hated walking past the slot machines and seeing people turning good money into bad.

They moved on from Atlantic City to New York and then Knoxville, Tennessee and Myrtle Beach, a resort in South Carolina. In New York, Tom took them to the renowned Harry Cipriani restaurant on Fifth Avenue near Central Park. Glynis turned to Dai and said, ‘Doesn’t that look like Danny DeVito over there?’

Tom piped up, ‘It is Danny DeVito. Watch now, he’ll ask me for a cigar.’

They had acted together in Mars Attacks! and got along famously. Sure enough, Danny came bustling over and asked for a cigar, but had no luck. Tom only had the one in his pocket and he was saving it for himself.

While Linda liked Atlantic City, she didn’t travel with Tom on this trip. He always made sure a ticket was bought for her wherever he was going, however, in case she changed her mind at the last minute and said, ‘I’m coming.’

The third time Glynis and Dai went on holiday to the US, Tom and Linda were moving house. They had decided that the home on Copa De Oro Road was too large for them, especially as Mark and his family were now based primarily in England. Linda was also becoming more concerned about security and her personal safety, and wanted to move to a property where there was more protection. She had never been entirely happy there, initially struggling with feeling homesick and then feeling both isolated and exposed at the same time. It was years before Tom met his next-door neighbour, a lawyer, and then it was at an awards ceremony in LA and not over the garden fence.

Tom once amusingly remarked that the house, which had always been known as Dean Martin’s, would only become Tom Jones’ when he moved. He sold it to the actor Nicolas Cage for a reported $6.5 million and then proceeded to spend $2.7 million on a more modest five-bedroom home in a gated community off Mulholland Drive, not far from Freda and Sheila. The refurbishment and interior design were something Linda was looking forward to. Best of all, their new home had spectacular views across the San Fernando Valley. One thing the new home was missing was their famous red phone box. They accidentally left it behind.

Glynis and Dai were expecting to stay with the Joneses when they arrived in August 1998, but the new house wasn’t ready yet, with many belongings still in boxes, so they stayed at an apartment in Santa Monica. In any case, Tom wasn’t there at first. He was in Dublin, filming a small role in Agnes Browne, which starred Anjelica Huston as the title character. Huston plays a salt-of-the-earth mother of seven, whose secret passion is Tom Jones. Near the end of the film, her dreams are fulfilled when Tom pops up to serenade her with ‘She’s a Lady’ – at least it wasn’t ‘It’s Not Unusual’ again.

The film was based on the book The Mammy by the Irish writer and comedian Brendan O’Carroll. He later began playing the part himself in Mrs Brown’s Boys, one of the biggest television comedy hits of recent years. In 2014, the character Agnes returned to the silver screen in Mrs Brown’s Boys D’Movie.

Tom was concerned about playing a younger version of himself. ‘I was slightly nervous having to look as I did in 1967, but Anjelica told me not to worry as it was a “surreal situation”.’

Linda, meanwhile, was happy to play host to Dai and Glynis in Los Angeles. Tom had arranged for them to have a driver, Kyle, during their visit, and he phoned ahead from the limo to tell Linda they would be arriving in five minutes, so she could be waiting outside to greet them. It was the first time Glynis had met her: ‘I was a bit in awe of meeting her, but there she was in a long T-shirt and pumps, and, like me, her roots needed doing.

‘We had been to Hollywood Boulevard earlier and bought loads of cheap T-shirts for the kids in our street back home. They were only $7 each. I told Dave that we should leave them in the car, because I didn’t want her to think we were cheapskates. But he took them in to show her and said, “Look, Linda.” And she told us that she liked to go to the thrift shops. She said, “Nobody knows who I am, so I can just browse.” She was so down to earth. She made us lunch and we sat around a beautiful marble kitchen table that was as big as the lounge in our house.’

They also went to see Freda and Sheila at their home, which was just across from Barry Manilow’s mansion. Freda was confined to bed, having become progressively weaker in the past couple of years after being diagnosed with breast cancer. She had always loved the climate in California, but hankered to spend her final years back in South Wales. Sadly, now eighty-four, she was too ill to make the journey. Her daughter Sheila became her full-time carer, even though Tom would have provided the best help money could buy for his mum.

Tom flew into Las Vegas after his commitments in Dublin and they spent time with him before coming home. Glynis asked Tom if he had spoken to Linda since he landed and he told her his wife had rung him that night. She had been out for lunch. Then he laughed, ‘My wife is the only woman I know who would take the cook out for a meal.’

The couple who looked after the house and garden had been with Tom and Linda for years and they were her friends. Linda doesn’t have any superficial showbiz friends and prefers the company of these ordinary people, whom she knows and likes. Glynis observes, ‘Dai knew them. They are good people and they are loyal and that speaks volumes.’

They flew home to the UK happily unaware that it would be Dai’s last visit.

‘Tell me it’s not true,’ said Tom when Glynis came to the phone.

‘I wish I could,’ she replied, her voice catching in her throat.

Dai Perry, Tom’s best friend all his life, had been found dead on the mountainside behind Treforest. It was January 1999, and he was just fifty-eight. He had died a morning walk away from Laura Street. Tom was devastated by the loss of a man he loved as a brother.

Glynis knew there was something wrong when she arrived home from work and Dai wasn’t there. Every morning he would take Cassie, a neighbour’s gun dog, for a walk up the mountain, so she dashed across the road to see if the dog was there. She was, and the neighbour told her that she had accidentally shut Cassie in the lounge, so Dai must have set off by himself when he didn’t see her in the hallway.

Glynis ran back and discovered that his walking clothes and the binoculars that always hung round his neck were missing. Her last hope was that he was with Tom. Sometimes, out of the blue, Tom would show up at the house and take Dai off on a trip to London, but she knew he would have changed first. She decided to go and look for him, but when she opened the front door a police car had pulled up outside the house. Dai, who’d had a heart bypass operation four years earlier, had just keeled over while he was on his walk. He had been found by the local farmer.

Tom listened while Glynis told him what had happened. He then rang a couple of times a day to make sure she was all right and to find out how the arrangements for the funeral were progressing. He told her to keep her chin up, but was obviously very upset himself. She discovered that Lloyd Greenfield, Tom’s great ally and friend for thirty years, had died in New York five days before Dai.

When Tom rang on the Sunday night, the da

y before he was flying in, Glynis asked him if he wanted to say ‘ta-ra’ to Dave in the Chapel of Rest. Tom said that he did. She recalls, ‘I rang the undertaker and told him that a friend of Dave’s was coming in the morning to see him before he was moved. The carpenters who were working there were just having their tea break, when a people carrier with tinted windows drew up and out stepped Tom. The undertaker told me afterwards they nearly choked on their sandwiches.’

After he had said his goodbye, Tom, who had Mark with him that day, went round to comfort Dai’s mother, Elsie, who still lived in Laura Street. Then he went to the house in Lower Alma Terrace to see Glynis and set off for the funeral. It was the same house he had bought for Dai and his second wife Kay all those years ago. Glynis will never forget it: ‘He just looked at me and he burst into tears and I did. And we were just holding each other and everybody just disappeared around us and left us.’

Then it was time for the funeral at the nearby chapel. Tom travelled in the car with Glynis, her son David from her first marriage, and Dai’s daughters, Nicola and Gemma. A local councillor had arranged for them to have a police escort and in Treforest another policeman stopped the traffic to let them pass – something Dai would have loved.

At the chapel, Tom sat between Gemma and Glynis and ‘sang his heart out’, especially when it was time for his favourite hymn, ‘The Old Rugged Cross’. Glynis recalls, ‘That’s the one he sang the loudest. You could tell by the tremor in his voice that he was finding it hard, but he kept going.’ He had to lend Gemma, who was fifteen, a hankie to dry her eyes.

Afterwards, they went to the graveside for the burial and Cassie the dog sat patiently between Glynis and Tom while the vicar gave the blessing. On the way back to the cars, it was more like a wedding, with photographers taking pictures of Tom and Dai’s family. They tried to take pictures of Tom and Glynis at the wake at the Wood Road, but she refused.

Tom stayed late at the club and made sure he spoke to everyone. He sat on a sofa next to Gemma, who told him, ‘You smell like my dad.’ They both used the same cologne, called Secret of Venus by Weil. He danced with her to the Aqua hit ‘Doctor Jones’, which made them both laugh. He danced with Glynis as well, to a song more fitting to end the saddest of days – ‘Green, Green Grass of Home’.

20

Reloading

The inspired pairing of Tom and Robbie at the 1998 Brit Awards didn’t lead directly to Reload. The publicity helped the public accept an album of duets as a good idea, but the impetus initially came from a satirical record called ‘The Ballad of Tom Jones’, which was an unexpected hit that year.

By a strange twist of fate, the song was written by a musician whose real name was Tommy Scott. He was the lead vocalist with Space, an indie band from Liverpool. They had made the charts a couple of years before with ‘Female of the Species’, a track Tom liked and included in his stage shows. Tommy had been inspired when he saw Tom in concert in Manchester, performing his song: ‘All the housewives were screaming for Tom – but no one had a clue who I was.’

‘The Ballad of Tom Jones’ was a duet sung by Tommy Scott and the husky-voiced Welsh singer Cerys Matthews, whose band Catatonia were at the forefront of Britpop in the nineties, with hits including ‘Mulder and Scully’ and ‘Road Rage’. Tommy and Cerys play a squabbling couple who stop short of murdering one another when they start listening to Tom Jones’ Greatest Hits. Cerys memorably sang on the chorus, ‘I could never throw my knickers at you.’ She was voted the sexiest woman in rock in a Melody Maker poll, and Tom would probably have had no objection if she had thrown them at him.

The song was a huge hit, supported by an atmospheric video, and made number four in the UK charts. Tommy Scott described it as his ‘Frank and Nancy Sinatra thing’. Tom was flattered to have a song named after him. He commented, tongue in cheek, ‘You know you’re doing something right when they start recording songs about you.’

After the Brit Awards, Mark Woodward was very keen for his father to record an album of duets. He wanted to take advantage while everyone was talking about Tom and Robbie. Independently, Gut Records, the label that had released ‘The Ballad of Tom Jones’, had been thinking the same thing. They wanted to make a record with Tommy Scott and Tom Jones together. That was the original idea and it grew from there.

Gut had quickly built a reputation as one of the leading independent labels under the direction of a former radio plugger called Guy Holmes, who had started his own company to release ‘I’m Too Sexy’ by Right Said Fred. He contacted Mark at exactly the right time and an album of duets was swiftly agreed over dinner with Tom.

The only surprise was that it had taken so long for the idea to be conceived. Ten years had passed since Tom’s collaboration with the trendy The Art of Noise. Clearly the concept worked, as his duet with Robbie demonstrated. Now it was a case of deciding which artists to approach. That proved to be the easy part, because there seemed to be a queue around the block of credible artists wanting to perform with Tom. There was talk of All Saints joining him for ‘What’s New Pussycat?’, but that never materialised. It might have breathed new life into the old song, but would probably have been a step back in time and Tom was anxious to avoid that. In the end, seventeen acts made the final recording.

Robbie didn’t hesitate to sign up, even though he was understandably nervous about joining The Voice in the same vocal booth. They chose to record ‘Are You Gonna Go My Way’, a guitar-led track by Lenny Kravitz that was proving to be one of the highlights of Tom’s current stage show. Robbie revealed how he handled it: ‘I thought, “I know, I’ll do an impression of him”, so I did and I think I pulled it off.’ The first time Robbie had sung the complete song was on their initial run-through. That was the only chance he got. After they had finished, Tom announced, ‘That’s it, then. Shall we go to the pub?’

Robbie was on his way to becoming an international superstar, but he never achieved notable fame in the US. Tom did his best by introducing his friend as a new British star at one of his Vegas shows. Robbie stood up and took the obligatory bow, but nobody really knew who he was.

Robbie’s vocal concerns about singing with Tom were echoed by some of the other sixteen guests on Reload. Nina Persson, the blonde pin-up singer of The Cardigans, was scared she would sound ‘like a little moth’ next to Tom. She need not have worried, because Tom gave her the space to sing. The result was a quirky but memorable version of the Talking Heads song ‘Burning Down the House’. It set the mood for an album that would include some unexpected song choices, which sounded entirely different from the originals.

The Australian singer Natalie Imbruglia was another talented female vocalist concerned she would be overwhelmed by the power of Tom’s voice. After the first take, she felt like she had been caught in the path of a hurricane, but Tom subsequently reined back to give her a chance. They sang ‘Never Tear Us Apart’ by INXS, a poignant tribute to the singer Michael Hutchence, who had been found dead in November 1997. Tom had become friendly with Hutchence before he died and attended his funeral in Sydney.

Other singers were not so nervous. Mick Hucknall from Simply Red joined him to update the blues classic ‘Ain’t That a Lot of Love’. The two men enjoyed singing together so much that they sang a series of impromptu duets at a television party in September 1999 – ‘Delilah’ and ‘Green, Green Grass of Home’ featured, as well as Mick’s number one hit ‘Holding Back the Years’. It was like a night from the old days in Las Vegas. Tom thought Mick was one of the few singers who had ‘got the pipes’.

Another who certainly did was Van Morrison, who provided his own song, the melancholic ‘Sometimes We Cry’, for the album. Tim de Lisle, in the Mail on Sunday, noted, ‘The best guest, improbably, is Van Morrison, who has the lungs to keep up with the Jones boy and the clout to keep him under control. They deliver a touching, experience-tinged version of Morrison’s own ballad.’ Van shared one particular characteristic with Tom that made it much easier for the two men to wor

k together: he liked to record things in one take.

Tom had seldom been inclined to follow Van’s example and write his own songs. ‘Looking Out My Window’, however, was one of only a handful he had composed up to that point. Tom has always been too busy singing and performing to do any writing. As a young man, he was a gregarious figure and not one to shut himself away, finding meaningful chords on his guitar. He put his emotion into words other people had written. The poorly educated youngster had long ago grown into a well-travelled, entertaining man of the world with a lifetime of experiences he could put into composing – but he chose not to. He built the house, he didn’t design it.

He had written ‘Looking Out My Window’, a funky jazz track performed with the James Taylor Quartet, while staring at the pouring rain from behind his car windscreen in the Cromwell Road, London. The lyric is about a man wondering why his love has left him, but there is no suggestion that there was anything autobiographical in the lyric. It had originally been the B-side of ‘A Minute of Your Time’, one of his lesser hits from 1968.

Tom was keen to surround himself with the cream of Welsh music for the new album. He was quick to sign up Stereophonics, Cerys Matthews and James Dean Bradfield, the lead singer with Manic Street Preachers – they were the only three Welsh acts he knew. He met the boys from Stereophonics when they came to watch him in concert in Cardiff. Afterwards, they joined him for a drink and he asked them if there was any chance of them taking part. He returned the compliment by going to see them at Wembley Arena in December 1998. They went for drinks and Tom spent three and a half hours telling them stories about Elvis, having a crack in Vegas and some legendary drinking. They were spellbound. When they left, Tom told them, ‘Thank God, you’re going. I’ve run out of stories to tell you.’

Tom enjoyed their company and their music. When Mark and his family travelled to Los Angeles to spend Christmas with his mother and father, he phoned the drummer Stuart Cable to tell him that at that very moment Tom was sitting by the pool, listening to the group’s first album, Word Gets Around. In a sad postscript, Stuart died in 2010, aged forty, at his home in Llwydcoed, a village fifteen miles north of Treforest. He had choked on his own vomit after a bout of drinking.

Kim

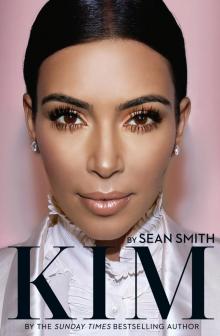

Kim Tom Jones - the Life

Tom Jones - the Life Kim Kardashian

Kim Kardashian