- Home

- Sean Smith

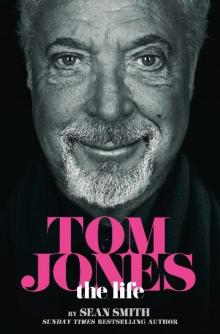

Tom Jones - the Life Page 12

Tom Jones - the Life Read online

Page 12

Tom was enjoying an old-style family Christmas, although some things had changed. He drove down in the Rolls with Linda’s present packed in the boot – a full-length fur coat. He joined everyone down at the Wood Road, where he discovered that the club had elected him honorary president. He had a ‘smashing’ time, so different from the depressing visit home two years before.

Chris was most impressed by how natural Tom was in his home environment. He met Tom’s sister Sheila, who was lovely company, and her husband Ken, who was bald and once gave everyone the biggest laugh of the year when he turned up in a badly fitting wig. ‘I can name some stars who were embarrassed by their family because they were ordinary people who said ordinary silly things.’ But not Tom: ‘He was very comfortable. His mother was fabulous. She was a loving woman. They were all very proud of him.’

Chris was always looking for an offbeat story that reflected his charge’s masculinity. When Tom spent most of his time in the US, it became more important to find the right picture on his trips to the UK. One day, when Tom was home, Chris rang a local photographer called David Stein and invited him round to take photographs at Gordon’s house. He had moved into a mansion on St George’s Hill, Weybridge, and sentimentally called it Little Rhondda. The grounds were big enough for him to fulfil a lifelong dream and install a small zoo.

David arrived and asked, ‘What’s the picture?’

Chris answered, ‘Tom, in Gordon’s tiger cage with the tiger.’

Understandably, Tom wasn’t keen. ‘He looked at the tigers and said, “No way.” And Gordon said, “They’ll be all right.” So we went to the cage and Tom said, “You go in first if you’re so keen.” Gordon went in first, then called me in and I went into this cage full of Siberian tigers. Next, Tom nervously came over and went in. Then we called David Stein and the tiger leapt on his shoulders and pushed him into a corner. I shall never forget the zookeeper saying, “David has purple trousers on – he doesn’t like purple!” We laughed about that for months afterwards – the tiger who didn’t like purple.’

The album Green, Green Grass of Home reached number three in March 1967. Tom was beginning to mature into an artist who could, quite literally, sing anything. He included Ponty numbers like ‘Riders in the Sky’ and ‘Sixteen Tons’, as well as the title track and the follow-up, ‘Detroit City’. Tucked away on side two was a little-known song called ‘All I Get from You Are Heartaches’, which perfectly captured the essence of Tom Jones: a vocal range that began smokily deep and soared to a perfectly pitched falsetto note – a very rare occurrence in one of his songs. The passion was evident.

This was arguably his golden age as a recording artist – certainly in the first half of his career. In July 1967, he released a track that he has often said is his favourite among all his recordings, the unforgettable ‘I’ll Never Fall in Love Again’. Tom still loves the song that was co-written by Lonnie Donegan, a very popular name from the fifties, who was the ‘King of Skiffle’ and topped the charts in 1960 with ‘My Old Man’s a Dustman’.

He told Tom that he had a song that ‘he could sing the pants off’. They met at Lonnie’s house in Virginia Water, near Ascot. Tom immediately thought it was ‘a wonderful song’ and has never changed his opinion. Lonnie was completely right. ‘I’ll Never Fall in Love Again’ was the first of three great power ballads that Tom released in a row, all of which reached number two in the charts. He sang the hell out of them.

The second of the trio was ‘I’m Coming Home’, another emotional song that he could have dedicated to Linda – ‘I am coming home to your loving heart.’ Les Reed and songwriting partner Barry Mason wrote it especially for Tom, knowing that he was the only singer who could do the song full justice.

For the recording at Decca Studio Number 2 in West Hampstead, Tom was keen to stand in the string section, which, as Les recalls, was unheard of, because of sound separation problems. ‘We agreed he could try. On the first go, he sang with such emotion that the whole orchestra, including myself, had tears in our eyes. It was an incredible performance.

‘Eventually the engineer’s voice came through – “That was terrific, Les … Are you ready to do a take?” Poor Tom collapsed in frustration.’

Chris joined Tom in New York after New Year’s 1968. One night, an executive with London Records, Lenny Marcel, took Tom to the Copacabana, the Upper East Side club widely referred to as ‘the Copa’. The singer Jack Jones and his famous father, Allan Jones, were both on the bill and the latter made a facetious remark about Tom: ‘We’ve got a hit-maker in the audience tonight. Tom Jones from England. Let’s find out if he can sing.’ So they called him on stage and Tom turned to Tony Cartwright and asked, ‘What can I sing? They won’t know any of my stuff.’ Tony suggested he perform the one song he always did a cappella – ‘My Yiddishe Momme’. He sang his heart out. Chris Hutchins remembers, ‘He tore the place apart.’

Tom so impressed that night that Gordon was soon negotiating a two-week residency at the club. This was the chance for Tom to try out a new image for the more mature market that Gordon was hoping to reach. He didn’t pack the leather trousers. Instead, he wore a black tuxedo and a large black bow tie. His clothes were as tight as ever, but they were classy.

The Squires were flown over for his opening night and rehearsed extensively with the club’s orchestra. Tom came across like a youthful and exuberant Sinatra, as he muscled his way through ‘What’s New Pussycat?’, ‘I Can’t Stop Loving You’, ‘It’s Not Unusual’ and standards including ‘I Believe’ and ‘Hello Young Lovers’. The highlight for many was a passionate rendition of ‘Danny Boy’ that reduced his audience to tears. Afterwards, Tom was elated and declared, ‘I’m so happy.’

That feeling wore off quite quickly when the reality of three shows a night in the smoke-filled, candle-heavy atmosphere of the club reduced its charms and put his voice under considerable strain. The Copa was a supper club for organised crime run by a legendary figure called Jules Podell. He never actually saw a show himself, preferring to spend the evenings in the kitchen, perched on a chair by the cash register. Tom’s last show was at 3 a.m., when he sang for an hour and a quarter. The schedule was the first sign of his Dracula lifestyle. For the next thirty years, he worked and played at night and slept through the day.

The headline act was the hired help; the people who mattered were sitting at the tables. Each night, the first thing Tom did when he arrived at the club was seek out his host and say, ‘Good evening, Mr Podell.’ It was a mark of respect. The tiny stage was so close to the tables that Tom was practically sitting with the clientele.

On one memorable occasion, he was so infuriated by one female guest’s incessant high-pitched prattle during his rendition of ‘Danny Boy’ that he jumped off the stage, thrust a microphone under her nose and suggested she finish the song. Luckily, she wasn’t the wife or mistress of an important gangster.

The club probably had space for little more than 150, but they were the cream of the New York underworld. Chris Ellis, who travelled with Tom, told the author Robin Eggar, ‘If the police had raided the place they’d have cleaned up New York in three seconds flat.’

One evening, a ‘button man’ came over to where Tom was drinking at a table. Tom, who had been told he needed to stand up for himself, had no idea who he was and said, ‘What the fuck do you want?’

The gangster replied, ‘Stand up. I want to see how big you are.’

Tom noticed he was being kicked under the table by his worried companions when he said, ‘I’ll show you how big I am.’

Sonny Franzese, one of the bosses and a ruthless killer, laughed and walked away, while Tom’s friends had nervous breakdowns.

The following year, Sonny came up to Tom when he was appearing in Las Vegas and said, ‘You’re the kid who told me to fuck off!’

Tom smiled and responded, ‘I am. And who wants to know?’

In the America of the 1960s, playing the Copa was a sign that you were a serious name i

n the music business. Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis, Jr, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis had appeared there often, but so had more modern acts, including Marvin Gaye, The Temptations and The Supremes, and the great female artists Peggy Lee and Ella Fitzgerald were always popular.

Tom’s spell at the Copa included an incident that had a life-changing effect on his career and how Tom Jones would be perceived for the next twenty years. Tom was sweating, because the heat in the club was stifling and, as usual, he was putting his heart into his performance. The audience at their tables were handing him their napkins for him to mop up the sweat. He recalled, ‘All of a sudden, this woman stands up, lifts up her skirt and whips off her knickers. She gives them to me to wipe my forehead.’ Tom entered into the spirit by accepting them and commenting, ‘Don’t catch cold.’

An entertainment columnist in the audience wrote about it and called Tom a ‘panty magnet’. Knickers became an unavoidable addition to a Tom Jones concert from that moment on. Over the years, he would grow to hate the ritual, because it reduced the attention given to his voice. He didn’t care about pants, but he was devoted to the music.

Moving from the Copa to a Las Vegas show was a natural progression. He was such a hit in New York that he attracted the attention of the rich and powerful of Las Vegas. Tom might have appeared there earlier than 1968 if Gordon had accepted offers for him to be a lounge act after The Ed Sullivan Show appearances. The money was attractive, but Jo strongly advised against it, because she had been to Vegas as a Bluebell Girl and knew how difficult it was to make the jump from lounge act to headliner.

In March, Tom transferred to the Flamingo Hotel, which wasn’t in the best of health and certainly wasn’t on a par with Caesars Palace. He was about to change that.

The underwear followed him to Vegas either by accident or design. Gordon was delighted, because it guaranteed some easy publicity. Chris Hutchins was ready with some sparkling one-liners for when Tom picked up one of the many pairs of lacy panties hurled in his direction. He would wipe his face and then declare mischievously, ‘I know this woman …’, which would be greeted by a roar from the now almost exclusively female audience.

The more intimate surroundings of first the Copa and then Vegas put a greater emphasis on Tom’s interaction with the audience – something that didn’t come naturally to him. He would have preferred to belt out song after song. Tom had a good memory for detail and was excellent at telling funny stories, but he wasn’t so adept at banter. He understood he needed to make the audience feel wanted, however.

The hotel was determined to make Tom the hottest ticket in town before he began. They needed to, because they had agreed to pay Tom a million dollars for three residences over an eighteen-month period. It was a considerable coup for Gordon and Lloyd, who took care of things for Tom Jones from day to day. The point of the entertainment was to bring punters into the hotel so they would gamble at the casino. The Flamingo’s publicity director, Nick Naff, devised ‘Tom Jones Fever’ as the hook for his campaign, which began by placing bottles of pills around the hotel labelled ‘Tom Jones Fever Pills’. They were guaranteed not to cure you, but could make the ‘fever’ more tolerable. Radio commercials leading up to his opening night gave daily updates on the Tom Jones Fever temperature, as if it were a wacky weather forecast. Astutely, Naff even placed an ambulance at the back of the showroom, in case any of the audience were overwhelmed by the fever. It was masterful.

The Flamingo wasn’t the biggest hotel on the strip and only 500 people could watch Tom at each of his two-nightly shows. The result was that, from the very beginning, there was always a long line of hopeful women queuing for a ticket. Most of them had a pair of knickers ready in their handbags.

12

A Love Supreme

If the eyewitnesses are to be believed, Tom had a voracious sexual appetite, unequalled in the world of entertainment, and all achieved without the aid of drugs – just a liberal dose of his now favourite Dom Pérignon champagne, a cigar or two that he didn’t inhale and a direct approach that worked most of the time.

Over the years, Tom’s libido has become a joke subject, which ignores the fact that he is married to a devoted wife. Sometimes the humour is unintentional. A television interview early in his career featured a voice-over that declared with old-fashioned solemnity: ‘For the successful pop singer, a grinding succession of one-night stands is the routine.’ It would seem that was the case with Tom.

The moment Tom shut the front door behind him, he was a single man. When he opened it again and announced he was home, he was married. Perhaps Gill Beazer was right and he just wanted the company of women and didn’t much like the prospect of spending a night alone.

The dilemma for Tom was that his publicity was promoting his status as a sex symbol, which once again pushed Linda into the background. From the first time he first wiped his brow with a pair of white knickers, he had a reputation that needed to be fed.

Considering the legend, he has managed to avoid a string of kiss and tells. With a few notable exceptions, he has bedded hundreds of women and yet could count on the fingers of one hand the number who have sold him down the river.

Occasionally, he met someone who meant something more. The first of the few was Mary Wilson, a founder member of The Supremes. They met in January 1968, when he knocked at her dressing-room door at the Bal Paree in Munich, where the Bambi Awards, the German equivalent of the Oscars, were being held. By coincidence, Tom had just recorded the group’s classic ‘You Keep Me Hanging On’ for his next album, 13 Smash Hits.

The introduction was engineered by the agent Norman Weiss after Tom mentioned he would love to meet her. Norman had booked The Supremes to perform at the ceremony. The glamorous Diana Ross was the undisputed lead singer of the famous girl group, but it was her sultry and more curvaceous bandmate who had caught Tom’s eye.

It really was love at first sight for Mary. Norman had mentioned Tom to her enough for her to take an interest. If Google had existed then, she could have typed Tom’s name into the search engine and quickly established that he was married. Instead, she had no idea and was ‘giddy as a schoolgirl’ at the prospect of meeting him, after she realised how good looking he was and how well he sang.

The spark between them was there right from the outset. In the mid-sixties, The Supremes were more famous internationally than Tom Jones, so Mary wasn’t some star-struck fan dazzled by a smooth celebrity. She described him tenderly in her autobiography, Dreamgirl: My Life as a Supreme. He was like no man she had ever met. ‘We talked, we cuddled, then we kissed, and by the time the evening had ended I knew I was in love.’ Mary was impressed that they would spend hours just talking. Tom may have been a man’s man, but he never lost his empathy with women.

Poignantly, Mary reveals that she believed she had found true love at last. She was single, unattached and struggling to come to terms with the death of Florence Ballard, another founder member of The Supremes, and the fact that the group had been taken over by Diana Ross. She was ready to fall in love.

The most telling aspect of their affair was that it was completely indiscreet. Right from the start, Mary would fly into the town where Tom was performing. She arrived in New York during his week at the Copa and got in the habit of dressing down and donning a pair of de rigueur celebrity sunglasses, but the couple were too famous to fool many people. They enjoyed the little private jokes that lovers do. If Tom rang and she was unable to answer, he would leave a message that Jimi Hendrix had called. She knew it was Mister Jones, even if her entourage thought she had hooked up with the famous guitarist.

As she remembers fondly in her book, she would fly to Vegas when he was playing the Flamingo and sit in the audience. He would quite openly sing songs just for her. One evening, he sang ‘Green, Green Grass of Home’ and, without pause, swung straight into ‘That Old Black Magic’.

Faced with such romantic gestures, it becomes easier to excuse her failure to break it off when she discovered Tom was

married. She may have felt like a fool, but it was too late. Instead, she flew to London, checked into the Mayfair Hotel and invited Tom over for the evening. He left the next morning. It was a routine they would follow many times when he was in the UK.

He would send over his new Rolls-Royce to pick her up. He now had two – a Phantom and a Silver Shadow. He would take her to pubs and then, more daringly, to some of the more fashionable restaurants in the West End, like Mr Chow. This was a celebrity Mecca in the sixties and not a place to go if you wanted to keep an affair quiet.

They may have been called the Swinging Sixties, but a man cheating on his wife with a beautiful black woman was still a move unlikely to win Tom any popularity polls back in the United States. There he was a relative newcomer, albeit a hugely successful one.

Despite his obvious affection for Mary, he wasn’t stringing her along. He liked being with her, but never suggested it was anything more than a fling. Mary was left under no illusion where she stood in relation to Linda during her trip to visit Tom in Bournemouth. He was appearing in a summer season at the seaside town’s Winter Gardens in June 1968. A line appeared in the gossip column in Disc magazine that Mary Wilson was back in the UK and she had come to see Tom Jones.

Linda, who liked to read the music papers, immediately phoned Chris Hutchins and asked, ‘How do I get to Bournemouth? Will you get me a minicab?’ When Chris asked her why, she replied, ‘I’ve just read this and I’m going down there to sort him out.’

Chris organised a car for Linda, who has never learned to drive, then phoned Tom and said, ‘Just get her out. Linda is coming down.’ Tom’s wife was a genuinely nice, quiet woman, except when she felt her position threatened – then she was a tigress.

Chris remembers, ‘He told me later that he flew around the place with Chris Ellis. They got Mary out and they went around and they removed every trace of her. And Linda came in and said, “Where is that woman, where is she?” And Tom said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” And she said, “Mary Wilson, she’s been here.” And he said, “No, she hasn’t.”

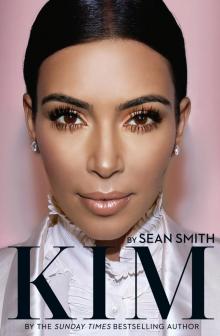

Kim

Kim Tom Jones - the Life

Tom Jones - the Life Kim Kardashian

Kim Kardashian